Favourite film of all time

- sanya khanna

- Oct 17, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Apr 26

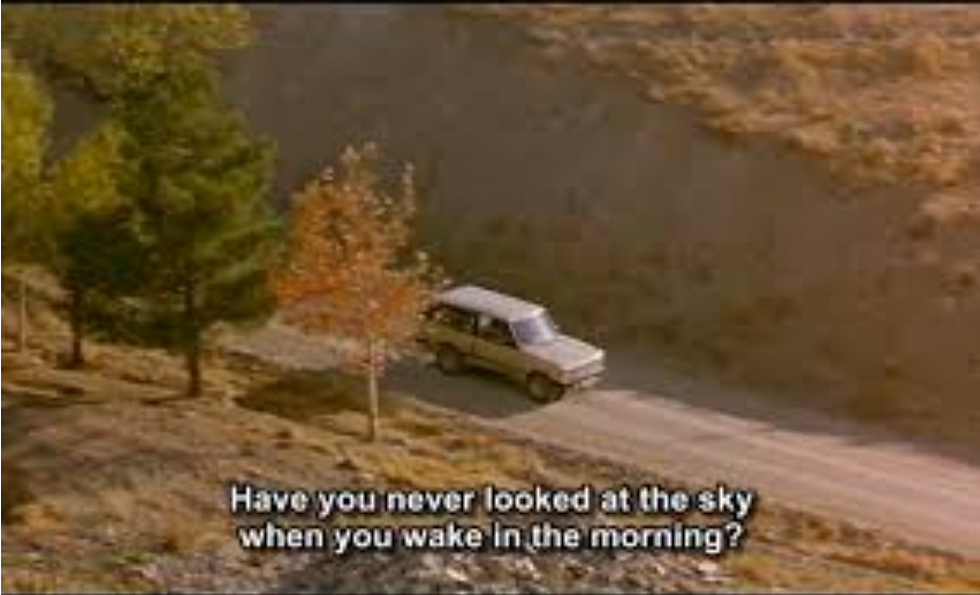

Taste of Cherry, 1997 by Abbas Kiarostami

A lot of films that talk about life and death usually convey their argument through dialogue and conflict between two or more characters. Look at the Before trilogy, Bergman’s prophetic Seventh Seal. However, for me, it is Abbas Kiarostami who takes the cake.

An Iranian director making a film on the forbidden subject of suicide must have taken some courage.

Although when we associate the word Iran and suicide, one cannot help but paint a picture of a suicide bomber, terrorist, or victim of war, the film shocks the international viewer by presenting just another run-of-the-mill man discontent with his life without addressing any backstory. In a nuanced world where everything has become highly topical, he probably didn’t want any labels to be associated with his main lead.

Nevertheless, he ensures to captivate the viewers with a series of amusing adventures involving the protagonist, one of which involves searching for someone who will agree to bury him after he commits suicide.

In this austere, emotionally complex drama, Kiarostami presents the enigmatic Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi) and his extended conversations with three passengers (a soldier, a seminarian, and a taxidermist), each symbolically representing different sectors of society and eliciting varied views on mortality and personal choice.

He shares his self-execution plan with each of them, saying, “Dig a pit, throw sand over my body and close it. If I answer, pull me out. If I don't, throw in 20 shovels of earth to bury me."

Upon hearing this, the serviceman flees, the seminarian declines because suicide is forbidden by the Koran, and then an elderly taxidermist. Ultimately, his search is fulfilled when he finds a man willing to do the task because he needs the money to support his son. However, his new associate soon attempts to dissuade him from committing suicide by delivering a speech on Mother Earth and her offerings, and recounting a significant incident from his life in which “an ordinary, unimportant mulberry transformed his life.”

Functioning simultaneously as a closely observed, realistic story and a fable filled with archetypal figures, Taste of Cherry invites the viewer to reflect on what often goes unnoticed in everyday life.

In Kiarostami’s cinema, which is notably humanitarian, conversations are lengthy, elusive, and enigmatic, often leading to misunderstandings of intentions.

Through the film's cryptic ambivalence and slow pace, Kiarostami acquaints his audience with a certain weariness experienced by the protagonist, making it one of the most significant films to date.

In his portrayal, the car is depicted driving for extended periods in the wasteland or parked overlooking desolate Iranian landscapes, which the director might have encountered while wandering the country in search of livelihood and meaning, much like many others in the nation. The viewer, alongside the lone smoking protagonist, intimately explores the city from the adjacent seat, allowing us to partake in his quest to find an end.

Ultimately, Badi's decision to commit suicide is not the main focus, hence the open and ambiguous ending. What truly matters are the choices we make and how we sustain ourselves during the bleakest times.

Kiarostami's cinema deeply respects the audience as a group of thoughtful, intellectual individuals. He never resorts to techniques designed to overtly stir emotions or edits didactically to make a political point, nor does he instruct through an obvious narrative structure. Instead, it is never self-serving but self-aware enough to be humbled by its own perspective in the face of both the existential and the spiritual.

The film strikes a chord with millions who’ve dealt with existential quandaries.

It explores the meaning people put on their lives by providing philosophical debates about whether suicide is right or wrong and encouraging new outlooks on life.

Weaving a protagonist who has developed his own theological morals, which stand in complete contradiction to the traditional outlook, one can’t help but applaud the stirrings of artistic independence in the strict Islamic republic.

Searching for answers or an end, the stoically paced minimalist narrative is not just a beautiful film, quaint with warming golden-brown hue landscapes, but a piece of life-affirming cinema.

Comments